Cubism, a revolutionary art movement that emerged in the early 20th century, reshaped the very foundations of artistic expression. Developed primarily by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Cubism introduced a radically new approach to visual representation, breaking away from the conventional norms of realism that had dominated Western art for centuries. Instead of depicting subjects as they appear to the eye, Cubism sought to portray them from multiple perspectives simultaneously, offering a more holistic view of the subject. This bold experimentation with form, perspective, and abstraction laid the groundwork for modern art and influenced countless movements that followed. But what exactly is Cubism, and what was the driving idea behind it? Let’s explore.

The Origins of Cubism

Cubism began around 1907 and reached its peak during the 1910s. Its inception is often linked to Picasso’s groundbreaking painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). In this work, Picasso abandoned traditional perspective and proportions, presenting a fragmented and geometric reinterpretation of the human form. Around the same time, Braque was exploring similar ideas, inspired by Paul Cézanne’s post-impressionist works, which emphasized the simplification of natural forms into geometric shapes.

The term “Cubism” itself was coined somewhat derisively by art critic Louis Vauxcelles in 1908. He described Braque’s work as being composed of “cubes,” referring to its blocky, angular aesthetic. Though initially intended as a critique, the name stuck and became synonymous with one of the most important art movements of the 20th century.

The Two Phases of Cubism

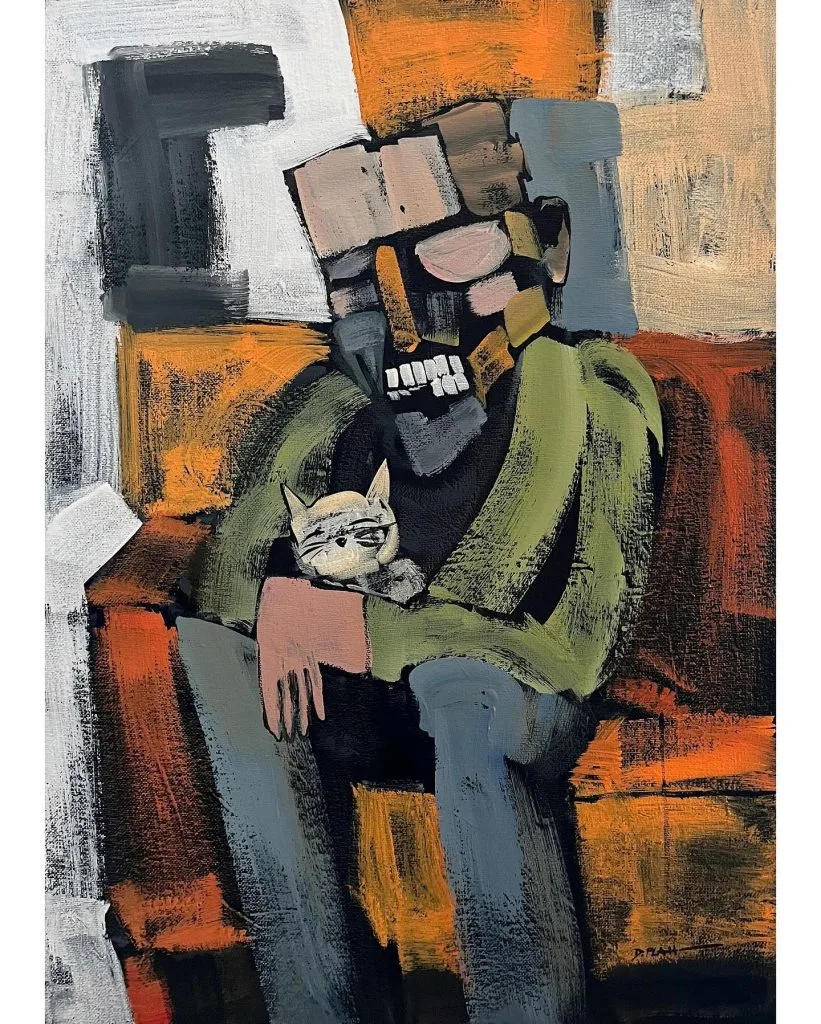

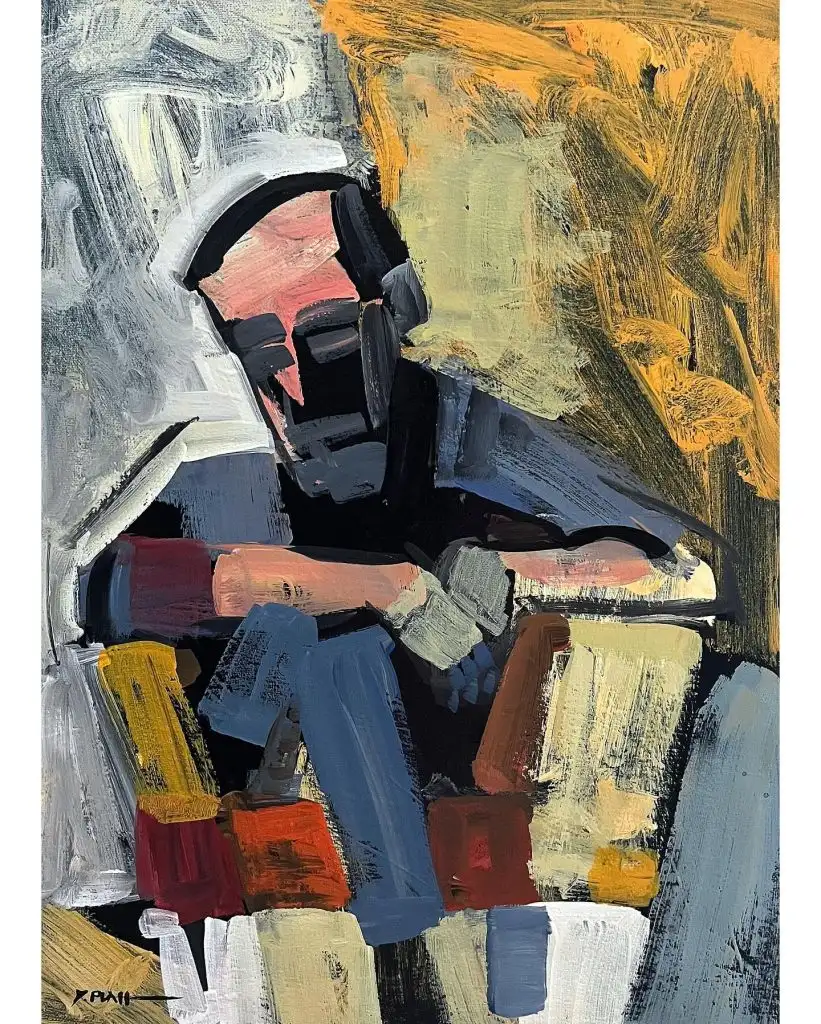

Cubism evolved in two distinct phases: Analytical Cubism and Synthetic Cubism. Each phase had its unique characteristics and objectives.

Analytical Cubism (1907-1912)

In the Analytical phase, artists deconstructed subjects into fragmented, geometric forms. They then reassembled these forms on the canvas in an abstract, almost puzzle-like manner. This approach often resulted in artworks that appeared complex and difficult to interpret at first glance. Analytical Cubism prioritized the exploration of multiple perspectives, light, and shadow within a single composition.

During this phase, colors were typically muted—shades of brown, gray, and ochre dominated the palette—to keep the viewer’s focus on form and structure rather than color. Famous examples of Analytical Cubism include Picasso’s Girl with a Mandolin (1910) and Braque’s Violin and Candlestick (1910).

Synthetic Cubism (1912-1920s)

Synthetic Cubism marked a shift towards more playful and accessible compositions. Here, artists began incorporating elements from the real world into their works, such as newspaper clippings, fabric, and other materials, creating the first examples of collage in fine art. This phase emphasized color, texture, and composition over the rigorous deconstruction seen in Analytical Cubism.

Synthetic Cubism allowed artists greater freedom to experiment with materials and techniques, often resulting in works that blurred the boundaries between painting and sculpture. Notable examples include Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning (1912) and Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass (1912).

The Core Ideas Behind Cubism

At its heart, Cubism was driven by a desire to challenge and redefine traditional notions of art and perception. Here are some of the core ideas that underpinned the movement:

1. Multiple Perspectives

Cubism sought to capture the essence of a subject by presenting it from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. This approach was a direct departure from the single-point perspective that had dominated Western art since the Renaissance. By fragmenting and rearranging forms, Cubist artists offered a more dynamic and comprehensive understanding of their subjects.

2. Abstraction and Simplification

While not entirely abstract, Cubism moved away from naturalistic representation. Objects were simplified into geometric shapes, and details were often omitted or stylized. This abstraction allowed artists to focus on the structural and conceptual aspects of their subjects rather than their superficial appearances.

3. Integration of Art and Reality

Cubism blurred the line between art and reality by incorporating everyday materials and objects into compositions. This approach not only challenged traditional artistic techniques but also expanded the very definition of what art could be.

4. Rejection of Traditional Aesthetics

Cubism rejected the idea that art should be beautiful in a conventional sense. Instead, it embraced complexity, ambiguity, and intellectual engagement. Viewers were encouraged to interact with the artwork, deciphering its fragmented forms and exploring its layered meanings.

The Impact of Cubism

The influence of Cubism extended far beyond the confines of painting. It revolutionized the way artists approached their work and inspired numerous other movements, including Futurism, Constructivism, and Surrealism. Cubism’s emphasis on abstraction and geometry also had a profound impact on architecture, design, and even literature.

For example, in architecture, the fragmented and angular forms of Cubism can be seen in the works of modernist pioneers like Le Corbusier. In design, the movement’s principles influenced everything from furniture to typography. Even in literature, writers like Gertrude Stein adopted Cubist techniques, experimenting with fragmented narratives and multiple perspectives.

Key Artists and Their Contributions

While Picasso and Braque are often credited as the founders of Cubism, many other artists contributed to the movement and helped shape its evolution:

- Juan Gris: Known for his refined and colorful approach to Synthetic Cubism, Gris brought a sense of harmony and balance to the movement. His work, such as The Breakfast Table (1914), often featured carefully arranged compositions with bold, vibrant colors.

- Fernand Léger: Léger’s version of Cubism, sometimes referred to as “Tubism,” incorporated cylindrical shapes and a more mechanized aesthetic. His works, like The City (1919), reflected the industrial and technological advancements of the time.

- Robert Delaunay: Delaunay introduced a sense of movement and rhythm to Cubism, blending it with his own style known as Orphism. His vibrant, colorful works, such as Simultaneous Windows (1912), celebrated light and energy.

Why Does Cubism Matter Today?

Over a century after its emergence, Cubism continues to be celebrated as one of the most influential art movements in history. Its emphasis on innovation and experimentation resonates with contemporary artists, who draw inspiration from its techniques and principles.

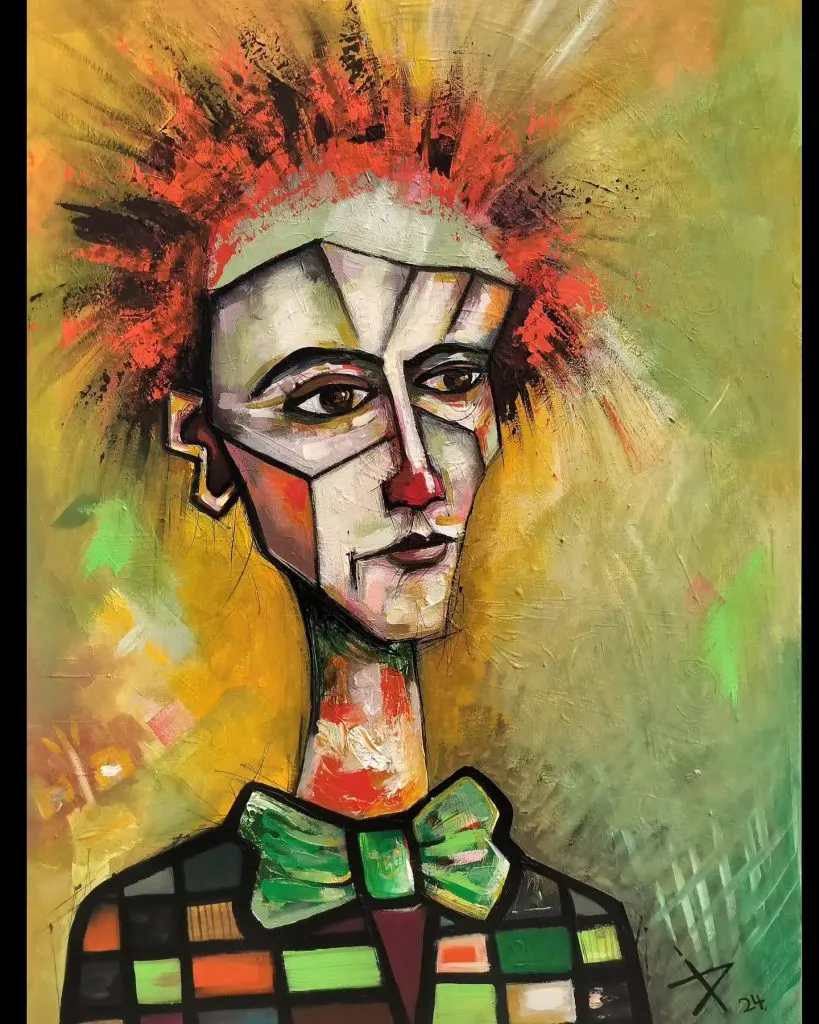

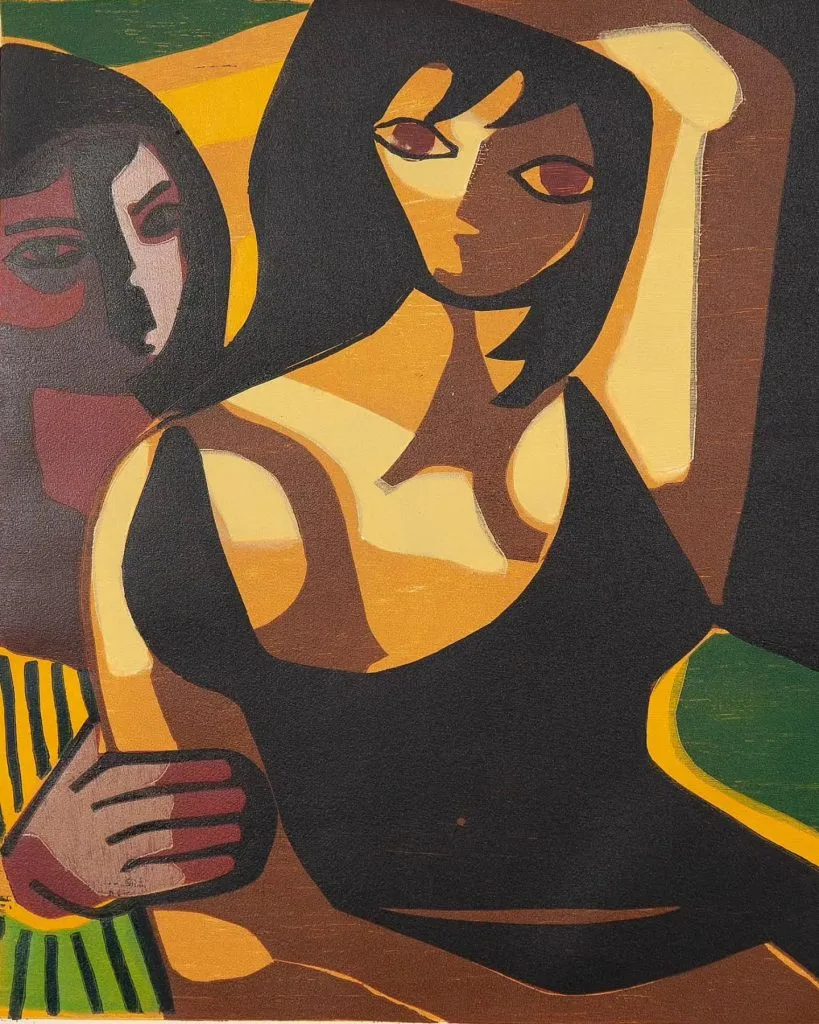

Inspiration Gallery for cubism art

See Abstract Art Ideas

In a broader sense, Cubism’s legacy lies in its ability to challenge established norms and encourage new ways of seeing and thinking. It reminds us that art is not merely about replication but about exploration, interpretation, and expression.

Conclusion

Cubism was more than just an art movement; it was a revolutionary way of understanding and representing the world. By breaking objects into fragmented forms and presenting them from multiple perspectives, Cubist artists challenged traditional notions of beauty, perspective, and realism. Their groundbreaking work laid the foundation for modern art and continues to inspire artists and audiences alike. Whether viewed as a historical milestone or a source of creative inspiration, Cubism remains a testament to the boundless possibilities of artistic expression.