Throughout the history of art, the female figure has occupied a central place as both subject and symbol. From the earliest fertility figurines of prehistory to the carefully rendered sketches of modern life-drawing studios, artists have continually returned to the body of the woman as a site of meaning, beauty, and creativity. Unlike other recurring motifs in art—such as landscapes or still lifes—the female form embodies both universal and culturally specific ideals. It has been used to represent fertility, divine power, beauty, sensuality, and even abstract concepts such as truth or justice. At the same time, the study of the female body has provided artists with a vehicle for exploring anatomy, proportion, perspective, and style.

The fascination with the female figure is apparent as early as the Cycladic statuettes from the third millennium BCE, whose simplified yet evocative forms demonstrate an early abstraction of womanhood into geometric ideals (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 22). Later, classical Greek sculptors such as Praxiteles would create more naturalistic yet equally idealized renditions, presenting the female nude as a measure of harmony and proportion (Janson 150). During the Renaissance, the revival of classical humanism inspired painters such as Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci to reconceptualize the female figure as both allegorical symbol and vessel of human beauty (Schneider 52). The theme persisted into the Baroque and Rococo periods, where artists like Rubens and Fragonard transformed the body into a spectacle of sensuality and dynamism.

In modern times, the female form has become a site of experimentation, fragmentation, and redefinition. With the rise of abstraction and psychology, artists such as Picasso and Modigliani shifted away from naturalism, exploring instead how the female body could express inner states of mind, cultural anxieties, or radical new approaches to form (Han 72). Yet, even amid such innovations, the practical study of the female figure remained foundational to the training of artists. Instructional texts, such as Francis Marshall’s Drawing the Female Figure, emphasized techniques of anatomy, foreshortening, and perspective to guide students in capturing the body accurately while also appreciating its aesthetic and expressive potential (Marshall 11).

Thus, the female figure in art cannot be understood as a static subject. Instead, it is a dynamic, evolving motif that reflects changing cultural ideals, artistic movements, and personal visions. This article will explore the journey of the female figure from its role in classical ideals to its place in the modern artist’s sketchbook, examining both its symbolic significance and its technical function in the study of art.

The Classical Ideal

The earliest artistic depictions of the female body in the Western tradition reveal a tension between abstraction and naturalism that continues throughout art history. In the Cycladic islands during the third millennium BCE, small marble statuettes of women were produced with strikingly modern simplicity.

The Female Figure from ca. 2700–2300 BCE, now housed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, emphasizes geometric reduction: the head is an elongated oval, the arms are folded across the torso, and the legs taper to points (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 24). These figures were not meant to stand but were often found lying in graves, suggesting a ritual or funerary role. Scholars debate whether they represented fertility goddesses, protective charms, or portraits of the deceased, but their enduring quality lies in how they distill the female form into balanced, harmonious proportions. They demonstrate that even in antiquity, the female figure was associated with ideals of life, continuity, and transcendence.

By the classical Greek period, the female body became central to a new philosophy of beauty and proportion. Artists such as Praxiteles advanced the tradition of sculpting the nude in naturalistic yet idealized form. His celebrated Aphrodite of Knidos—though known today only through Roman copies—was revolutionary as one of the first life-sized representations of a fully nude goddess (Janson 162). Unlike the abstract Cycladic figures, Greek sculpture sought to capture both anatomical accuracy and divine perfection. The female body became a measure of aesthetic and moral ideals, reflecting the Greek notion of kalokagathia, the unity of beauty and virtue. Even when clothed, as in the Kore figures of the Archaic period, the drapery was carved to reveal the body’s underlying rhythm and vitality.

Kalokagathia is a classical Greek ideal that represents the harmonious unity of physical beauty (kalos) and moral goodness (agathos) within a single, well-formed person.

Roman art inherited these ideals but often imbued the female figure with political or social significance. Portraiture became a tool of power, as rulers and their families were depicted with serene, godlike dignity. The Roman statue Portrait of a Ruler (ca. 200–225 CE), though headless, reveals the strong proportions and majestic stance that communicated imperial authority (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 47). While Greek art often aimed at an idealized universal type, Roman portraiture leaned toward individualized features, embedding the female form within social and historical context. Elite Roman women were portrayed with elaborate hairstyles, jewelry, and clothing, emphasizing both their wealth and their symbolic role as bearers of dynastic continuity.

The classical ideal of the female figure thus rests on a paradox. On one hand, it aimed for perfection—timeless proportions, symmetrical harmony, and divine beauty. On the other hand, it acknowledged the social and cultural roles of real women, whether as protectors of lineage, symbols of fertility, or embodiments of civic values. This duality would profoundly influence Renaissance artists who looked back to antiquity as a model for reinvention.

The Renaissance and the Reinvention of the Human Form

The Renaissance marked a pivotal transformation in how the female figure was represented in art. Rooted in the rediscovery of classical antiquity, Renaissance artists sought to combine naturalistic observation with the idealized proportions of Greek and Roman models. In this synthesis, the female body became not only an object of beauty but also a carrier of complex symbolic and allegorical meaning. Artists turned to the female form as a way to explore humanism, spirituality, and the interplay between sensuality and morality.

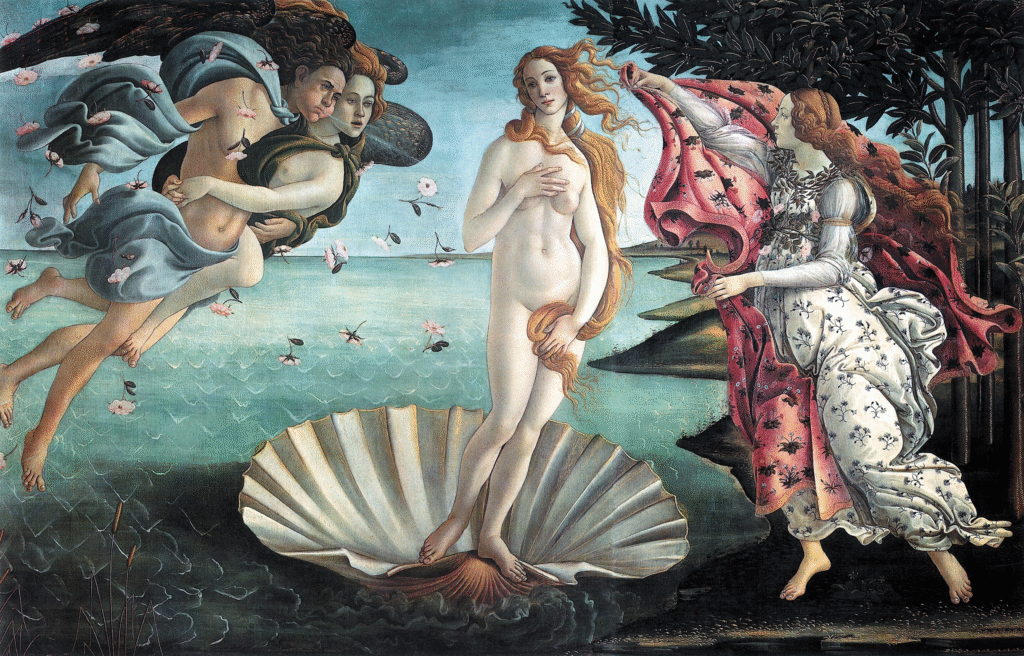

One of the most emblematic examples is Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (ca. 1485), which reimagined the mythological goddess as a vision of divine beauty emerging from the sea. Unlike medieval depictions of women that were often rigid and hieratic, Botticelli’s Venus embodies grace and delicacy, her elongated proportions emphasizing an otherworldly elegance rather than anatomical precision (Han 112). Renaissance artists such as Botticelli were less concerned with strict realism than with constructing an image that reflected philosophical ideals of beauty, inspired in part by the writings of Neoplatonist thinkers who equated physical beauty with spiritual truth.

At the same time, Leonardo da Vinci pursued a scientific approach to the human body, including the female form, through detailed anatomical studies.

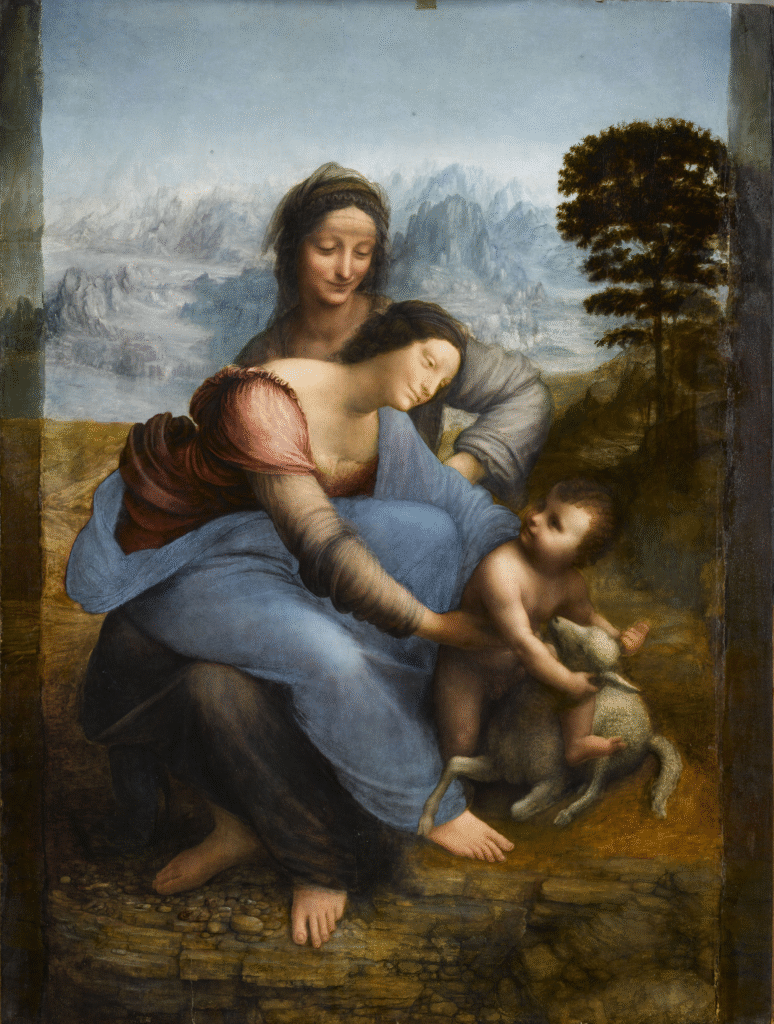

His drawings, such as the studies for Saint Anne with the Virgin and Child, reveal his effort to reconcile inner structure with outward appearance (World Fine Arts 13). Leonardo’s female figures often appear serene and introspective, their subtle gestures and enigmatic expressions inviting psychological interpretation. The most famous example, Mona Lisa (ca. 1503–06), epitomizes the Renaissance fascination with the mystery of the individual. Her smile, simultaneously intimate and elusive, transforms the portrait into a dialogue between viewer and subject, demonstrating how the female figure could embody both universal ideals and personal identity (Schneider 57).

Michelangelo, by contrast, approached the female form with the same heroic monumentality he applied to the male body. In his frescoes for the Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508–12), sibyls—female prophets from classical tradition—possess the muscular torsos and monumental presence of male nudes, a reflection of Michelangelo’s practice of basing female figures on male models (Janson 194). Though criticized for their masculine proportions, these figures highlight the Renaissance belief in the body as a vessel of divine power and knowledge. Michelangelo’s women are less about sensual allure and more about conveying strength, prophecy, and spiritual gravity.

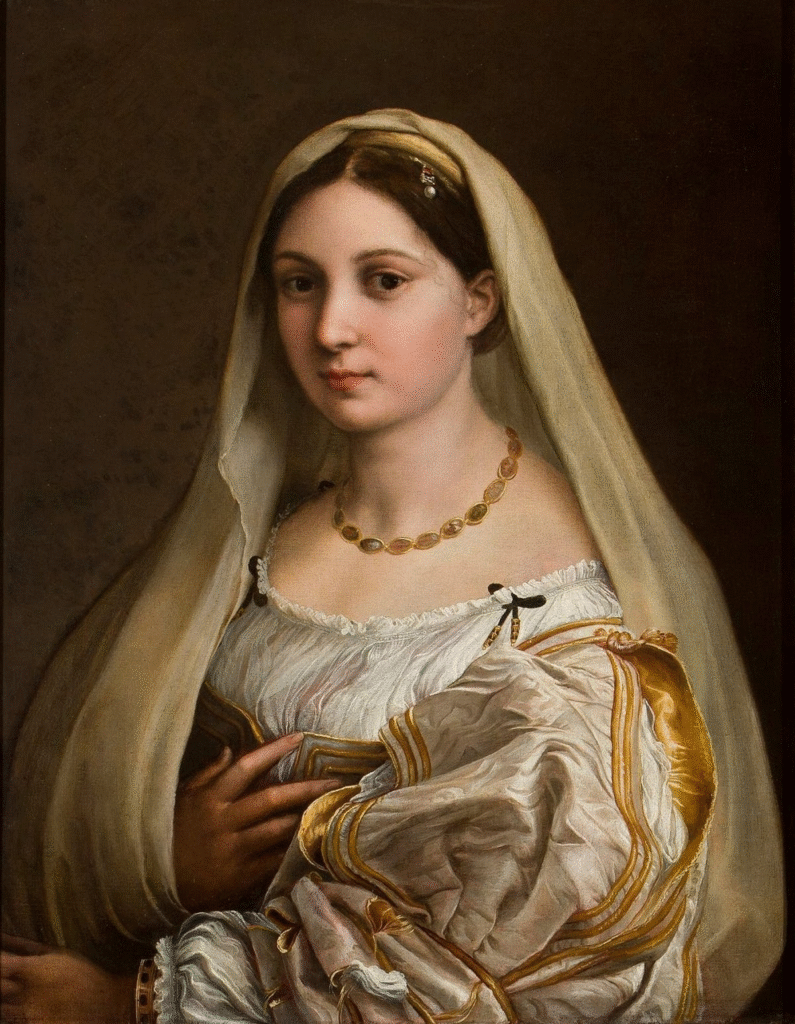

The Renaissance also introduced new contexts for the female figure through portraiture. Unlike medieval portraits that often emphasized status and piety, Renaissance portraits revealed the sitter’s individuality while still idealizing her features. Raphael’s La Donna Velata (ca. 1513), for example, presents the sitter with softness and grace, her veil and pearls suggesting marital virtue and social identity (Schneider 120). Portraits of noblewomen thus became not only likenesses but also visual affirmations of societal values, blending the personal with the allegorical.

Ultimately, the Renaissance reinvented the female form by fusing classical ideals of harmony with humanist attention to individuality. Women in art were depicted not only as muses or goddesses but also as intellectual figures, allegories of virtues, and subjects of intimate portraiture. In this period, the female body became a canvas upon which cultural, philosophical, and religious values were inscribed, setting the stage for the Baroque’s more dramatic and sensual explorations.

The Female Figure in Baroque and Rococo Art

If the Renaissance positioned the female figure as a balance between classical idealism and humanist individuality, the Baroque and Rococo periods heightened her role as a subject of drama, sensuality, and spectacle. Between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, artists across Europe embraced theatricality, movement, and emotional intensity. The female body, whether sacred, mythological, or secular, became the vehicle for communicating these qualities. Unlike the serene restraint of Renaissance Venus figures or sibyls, Baroque and Rococo women were depicted with exaggerated dynamism, radiant color, and unabashed sensuality.

The Baroque period, beginning in the early seventeenth century, was closely tied to the Counter-Reformation. Art was meant to inspire faith through awe and emotional engagement, and female figures often embodied this mission. Caravaggio’s paintings exemplify this shift. His Judith Beheading Holofernes (ca. 1599) presents a heroine who combines youthful beauty with ruthless determination, the chiaroscuro spotlighting her pale face against the darkness of the scene (Janson 342). Unlike Renaissance depictions that softened the violence of biblical heroines, Caravaggio’s Judith is at once sensual and terrifying, her physicality underscoring the dramatic realism for which the Baroque was known. Similarly, his David with the Head of Goliath (1607–10), though centered on a male figure, embodies the era’s fascination with flesh, light, and psychological intensity (History of Art 358).

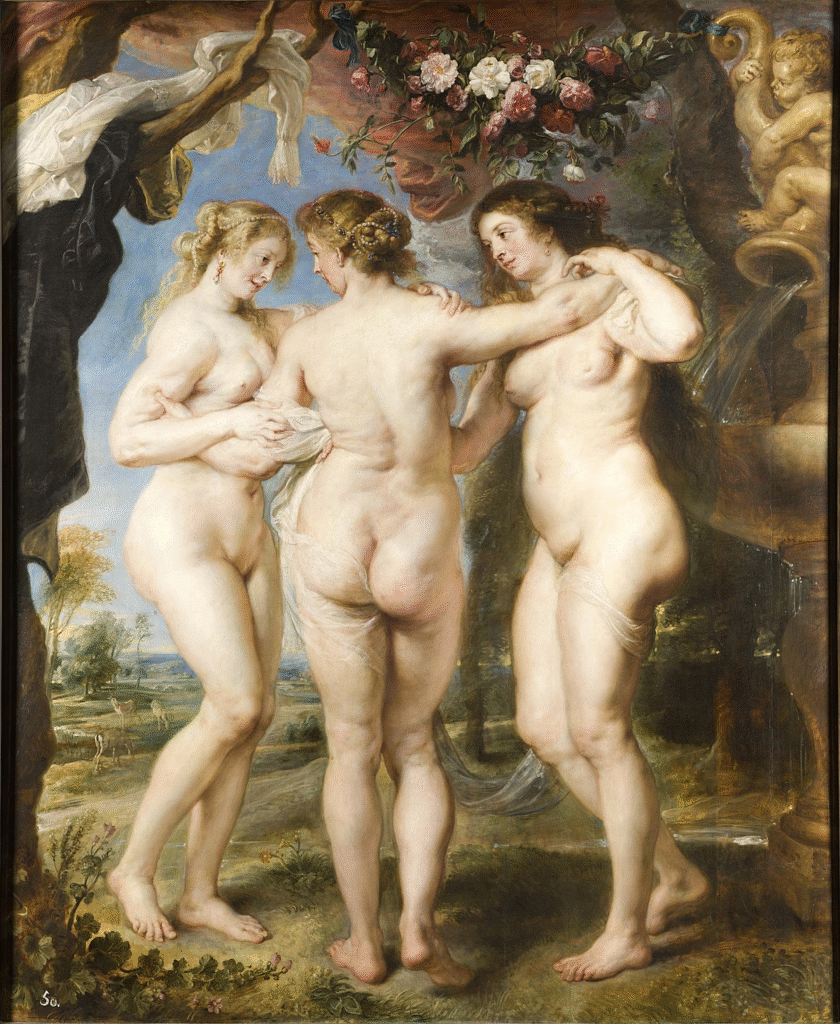

In northern Europe, Peter Paul Rubens epitomized the Baroque ideal of female sensuality. His voluptuous figures—now synonymous with the term “Rubenesque”—celebrated abundance, fertility, and erotic vitality. Works such as The Three Graces (1639) revel in the tactile qualities of flesh, depicting intertwined women as embodiments of beauty, pleasure, and divine harmony (World Fine Arts 27). Rubens’s women were not the slender, ethereal Venuses of Botticelli but robust, dynamic bodies that reflected the Baroque embrace of vitality and movement.

The Rococo period, which flourished in eighteenth-century France, brought a lighter, more playful treatment of the female figure. Where Baroque art conveyed grandeur and spiritual intensity, Rococo art emphasized intimacy, frivolity, and erotic charm. Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing (1767) captures this aesthetic perfectly: a young woman, dressed in frothy pink silk, kicks her slipper into the air while two men look on, one hidden in the shadows of the garden. The painting revels in feminine coquettishness, presenting the woman as both the center of desire and the orchestrator of playful deception (Han 145).

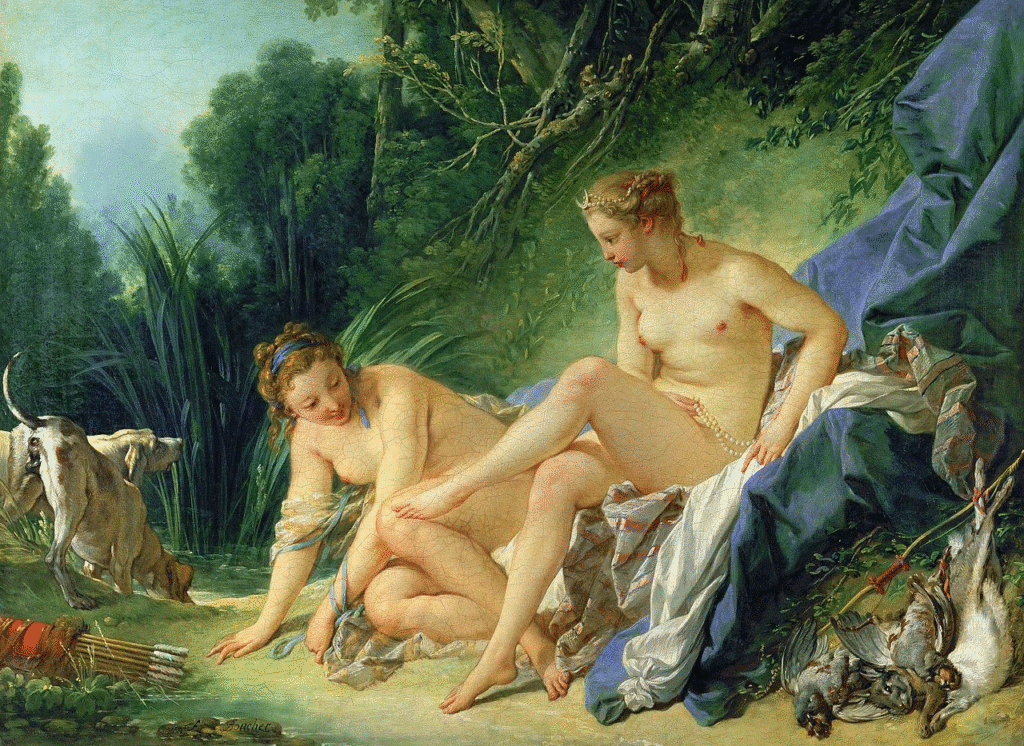

Even mythological subjects in the Rococo were reimagined with flirtatious elegance. François Boucher’s Diana Leaving the Bath (1742) presents the goddess of chastity as an openly sensual nude, surrounded by attendants and drapery that emphasize her softness. Here, the female form is not elevated as a divine ideal but transformed into an erotic spectacle for the male gaze (Schneider 162). This redefinition of the female figure reflected broader cultural shifts: the Rococo court culture of Louis XV, with its emphasis on luxury, pleasure, and artifice, encouraged artists to depict women less as allegories of virtue and more as embodiments of charm, seduction, and fashion.

It is important to note, however, that while Baroque and Rococo art often objectified the female body, these periods also witnessed women asserting themselves as artists. Figures like Artemisia Gentileschi brought new perspectives to traditional subjects. Her Judith Slaying Holofernes (1614–20) is more visceral and physically convincing than Caravaggio’s version, reflecting her lived experiences and offering a rare female interpretation of biblical heroism (Janson 350). In this way, the female figure was not only a subject but also a medium through which women artists could negotiate their roles in a male-dominated artistic world.

Together, the Baroque and Rococo periods amplified the expressive range of the female figure. She could be terrifying, as in Caravaggio’s Judith; voluptuous and triumphant, as in Rubens’s Graces; or playful and coquettish, as in Fragonard’s Swing. In all cases, the female body became a site of spectacle, inviting viewers not merely to contemplate ideals of beauty but to experience visceral reactions of awe, desire, or delight. This theatricality set the stage for the transformations of the modern era, when artists would once again challenge conventions of representation.

Modernism and the Fragmented Body

With the arrival of modernism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the representation of the female figure underwent a profound transformation. Where the Renaissance and Baroque had idealized or dramatized the female body, modernist artists fragmented, reinterpreted, and even deconstructed it. This shift reflected not only aesthetic innovations but also broader cultural changes: the rise of psychology, the trauma of industrialization and war, and evolving debates about gender and identity. The female figure, once the emblem of harmony or sensual spectacle, became instead a contested site of experimentation.

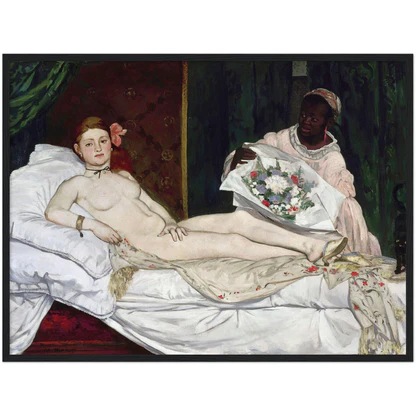

One of the pivotal moments in this transformation is Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863). Though chronologically situated before the height of modernism, the painting foreshadows its themes. Unlike Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538), which clothed sensuality in allegorical dignity, Manet’s reclining nude confronts the viewer with a direct gaze and unidealized body. Critics at the time were scandalized by her confrontational pose, pale flesh, and stark setting, interpreting the work as a critique of bourgeois morality (History of Art 912). Manet thus destabilized the classical nude, presenting the female body not as timeless beauty but as a socially and sexually charged presence.

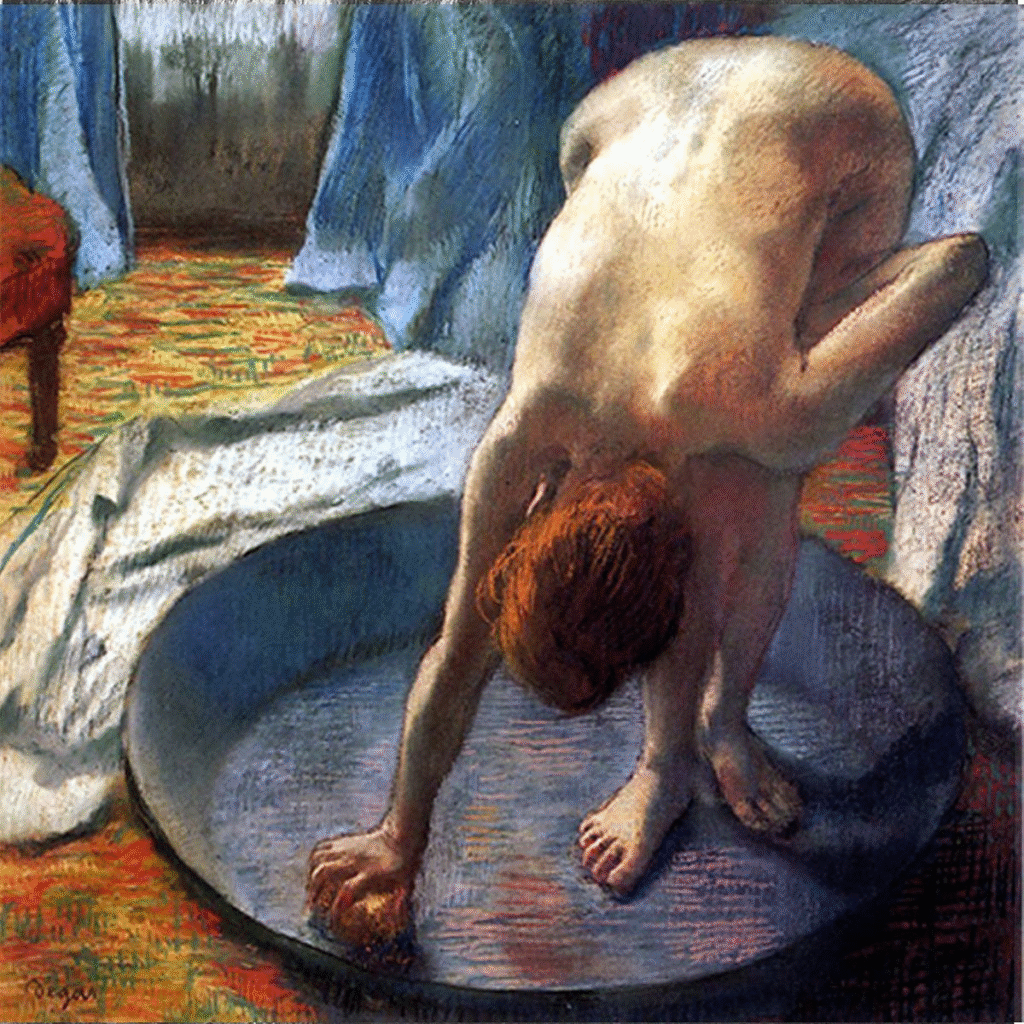

The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists further expanded this tension. Edgar Degas, for example, repeatedly depicted women bathing or dancing, often from unconventional vantage points. His The Bath (ca. 1885) portrays a woman hunched over in a basin, her body fragmented by unusual cropping and pastel strokes (World Fine Arts 57). Far from presenting a polished ideal, Degas emphasized the unguarded, awkward, and transient aspects of the body. Likewise, Paul Cézanne’s bathers are structured as interlocking forms rather than individualized figures, transforming the female nude into an exploration of geometry and color.

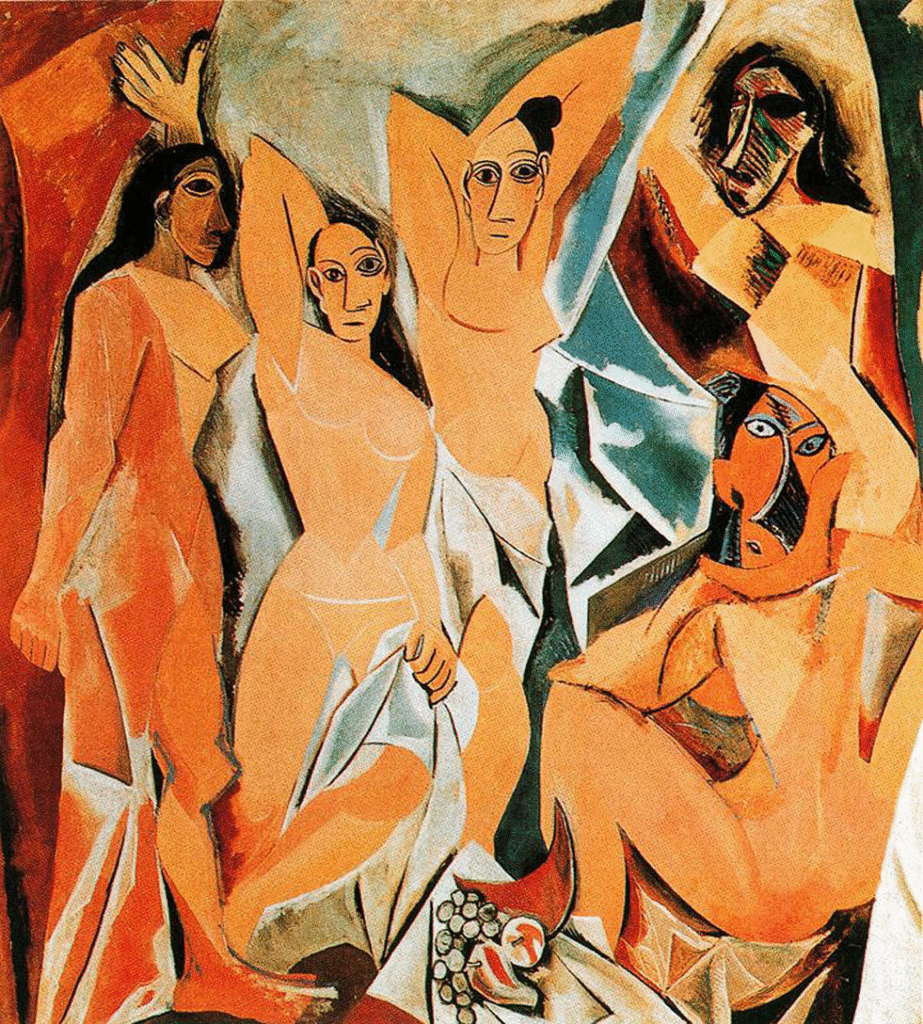

Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) represents a radical break with tradition. The painting depicts five nude women, but their bodies are fractured into angular planes and mask-like faces inspired by African sculpture. By rejecting perspective and naturalism, Picasso redefined the female body as a site of formal innovation and cultural critique. The work shocked contemporary audiences, not only for its raw eroticism but also for its dismantling of the Renaissance ideal of bodily harmony (Janson 958). Here, the female figure is no longer an object of beauty but a vehicle for exploring the anxieties of modernity and the possibilities of abstraction.

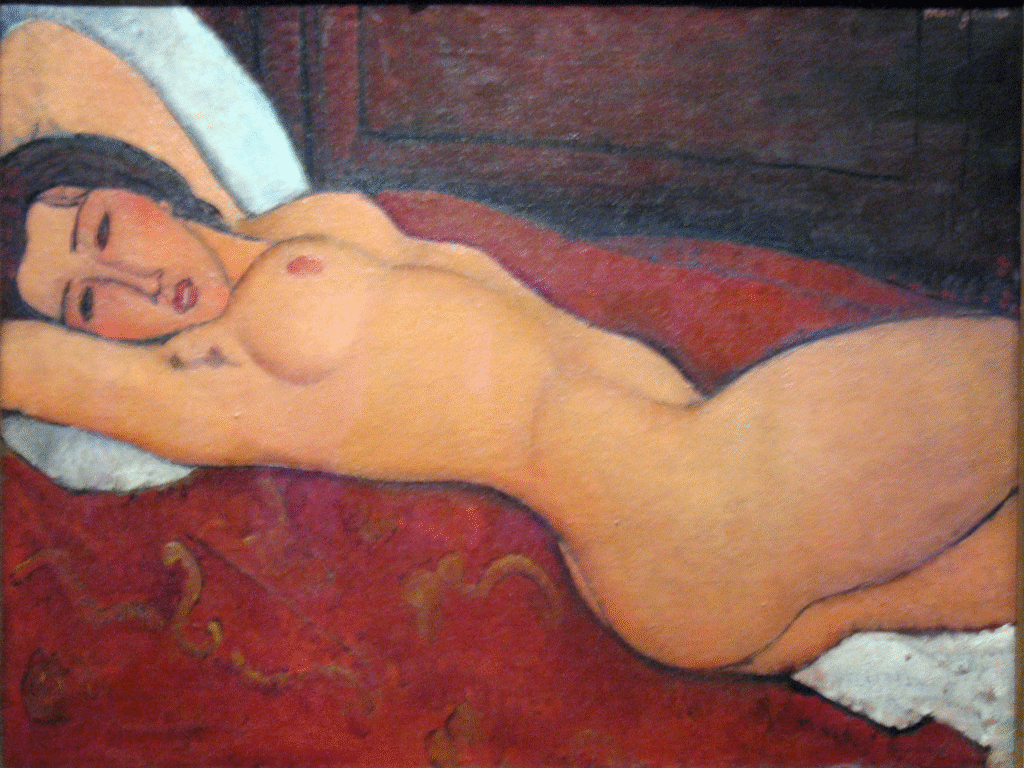

Amedeo Modigliani approached the female nude with a different modernist sensibility. His elongated portraits and reclining nudes, such as Reclining Nude (1917), retain sensuality but filter it through stylization. The long necks, simplified faces, and sinuous curves evoke both classical grace and modern elegance (Schneider 188). Unlike Picasso’s aggressive fragmentation, Modigliani’s distortions suggest an aesthetic of refinement, where individuality is subsumed into a timeless, decorative rhythm.

Meanwhile, modernist female figures often reflected psychological and emotional states rather than external ideals. The Surrealists, for instance, reimagined the female body as an embodiment of dreams, subconscious desires, and anxieties. Salvador Dalí’s Venus de Milo with Drawers (1936) literalizes this metaphor, transforming the classical goddess into a chest of drawers, a psychoanalytic parody of concealed desires. Similarly, Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits blur the boundaries between body and symbol, presenting the female figure as a vessel of personal suffering and cultural identity.

This modernist fragmentation of the female form was not without controversy. Some critics argue that works like Picasso’s Demoiselles perpetuated the objectification of women, breaking their bodies into parts for male artistic experimentation. Yet others contend that such works challenged traditional hierarchies, exposing the instability of beauty, identity, and sexuality in a rapidly changing world (Han 213).

Ultimately, modernism redefined the female figure as a site of rupture. Rather than offering unity or transcendence, artists embraced dissonance, subjectivity, and ambiguity. The female body became a mirror of modern anxieties—fragmented, unstable, and yet endlessly generative as a subject of artistic exploration.

The Artist’s Sketchbook — Drawing the Female Figure

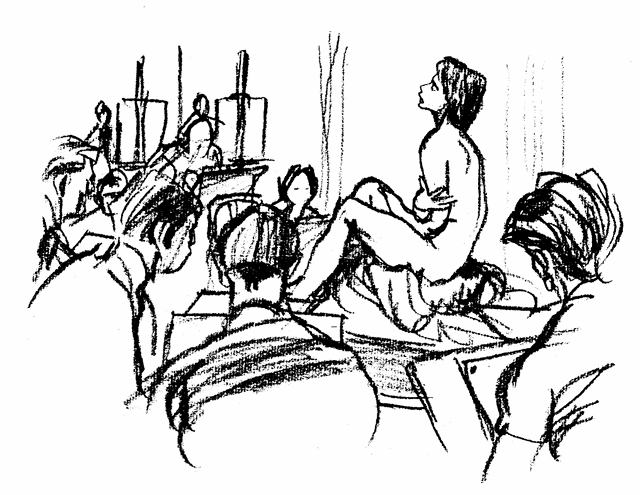

While the modernist era fragmented and reinterpreted the female body, the practical study of the female figure remained a cornerstone of artistic training. Regardless of whether the artist was a Renaissance master, a Baroque painter, or a twentieth-century modernist, the sketchbook became a laboratory for exploring anatomy, proportion, and expression. Francis Marshall’s instructional text Drawing the Female Figure (1949) is a vital document in this tradition, bridging centuries of artistic concern with contemporary pedagogical needs. In it, Marshall emphasizes both the technical demands and the aesthetic sensitivity required to render the female form convincingly.

Marshall begins with the fundamentals of life drawing, insisting that direct observation of the model is indispensable. He stresses that the female figure is not simply a matter of recording shapes but of understanding rhythm, balance, and weight distribution. “Life drawing,” he explains, “is not merely the copying of appearances but the translation of living movement into line and form” (Marshall 23). This principle echoes Renaissance notions of disegno—the belief that drawing was the intellectual foundation of all art (Janson 188). By situating the act of sketching within this lineage, Marshall underscores that figure drawing is both scientific and expressive.

A crucial component of his method is anatomy. In Drawing the Female Figure, entire chapters are devoted to the skeletal and muscular systems that underlie visible form. Marshall argues that without anatomical understanding, artists risk producing stiff or lifeless renderings. He illustrates how the curvature of the spine, the tilt of the pelvis, and the structure of the ribcage determine the outer silhouette (Marshall 85). This approach recalls Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical studies, which dissected the female body not merely for medical accuracy but to reveal how inner structures create grace and harmony (World Fine Arts 13). The continuity between Renaissance inquiry and modern instruction highlights the timeless role of anatomy in shaping artistic practice.

Marshall also devotes attention to foreshortening and perspective, two challenges that have tested artists since antiquity. He demonstrates how a reclining female figure appears compressed when viewed from the feet upward, producing distortions that must be consciously managed by the draftsman (Marshall 147). Similar problems preoccupied Michelangelo in his Sistine Chapel frescoes, where sibyls and nudes were rendered from sharply angled viewpoints (History of Art 194). By training students in these skills, Marshall’s manual functions as a bridge between the monumental achievements of Renaissance masters and the practical realities of studio practice.

Yet Marshall’s text is not purely technical. He also reflects on the aesthetic and cultural role of drawing women. In his chapter on beauty, he acknowledges the subjective and culturally conditioned standards that influence artistic choices. While Greek sculptors pursued proportionate perfection and Rubens exalted voluptuous abundance, modern artists confront diverse ideals of femininity (Marshall 201). He encourages students to observe individuality rather than chase an abstract canon of beauty, recognizing that the female figure is both a universal subject and a deeply personal one.

The emphasis on practice and observation situates Marshall’s work within a lineage of sketch-based learning. From the notebooks of Leonardo to the preparatory chalk drawings of Raphael, the female figure has long been a site where artists negotiate between idealization and realism. What Marshall provides is a codified guide for the twentieth-century student, reminding readers that mastery of the female form remains central to visual literacy.

In this way, Drawing the Female Figure reflects both continuity and change. On one hand, it affirms the long-standing tradition of treating the female body as a foundational exercise in proportion, anatomy, and perspective. On the other, it situates drawing in a modern context, acknowledging shifting ideals of beauty and individuality. By grounding artistic education in the female figure, Marshall demonstrates why this subject has persisted for millennia: it is at once technically challenging, aesthetically rewarding, and culturally resonant.

Check Out: The Evolution of Portraiture: From Jan van Eyck to Rembrandt

Conclusion

The history of art cannot be told without the female figure. From the abstract Cycladic statuettes of prehistory to the codified life-drawing lessons of the twentieth century, the female body has remained one of the most enduring motifs in visual culture. Across millennia, it has been idealized, dramatized, fragmented, and reinterpreted, each transformation revealing the shifting values of the societies that produced it.

In antiquity, the female figure symbolized fertility, divine power, and harmony, as seen in both Cycladic idols and the sculptural achievements of Greek and Roman art (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 24; Janson 162). The Renaissance reanimated these ideals through humanism, producing works such as Botticelli’s Venus, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, and Michelangelo’s sibyls, each of which blended observation with idealization (Schneider 52; World Fine Arts 13). In the Baroque and Rococo, the female form became theatrical, a site of spectacle and sensuality, from Caravaggio’s dramatic Judith to Rubens’s exuberant Graces and Fragonard’s coquettish young women (Han 145; Janson 350).

The modern period radically destabilized this lineage. Manet, Degas, Picasso, and Modigliani broke from naturalistic tradition to confront viewers with new questions about sexuality, psychology, and the instability of identity (History of Art 912; Janson 958). Modernism revealed that the female figure could serve not only as an emblem of beauty but also as a mirror of cultural anxiety, fragmentation, and subjectivity.

Yet throughout these stylistic revolutions, the female figure persisted in the artist’s sketchbook as a technical foundation and a test of skill. Francis Marshall’s Drawing the Female Figure demonstrates how, even in the twentieth century, students were expected to master anatomy, foreshortening, and rhythm through studies of the female form (Marshall 23, 147, 201). His manual reflects the enduring conviction that the body of the woman is not only a cultural symbol but also an essential exercise in perception, proportion, and artistic discipline.

Ultimately, the female figure in art is not a static object but a dynamic conversation across time. She embodies ideals of beauty and morality in one era, sensuality and power in another, and fragmentation and ambiguity in yet another. This adaptability explains her persistence: the female body has always provided artists with a site to explore the deepest concerns of their culture, whether those concerns are philosophical, spiritual, erotic, or psychological.

In tracing the arc from the classical ideal to the modern sketchbook, we see not a decline or loss but a continual reinvention. The female figure remains both subject and teacher, muse and model, symbol and study. In every age, she offers artists the opportunity to test their skill, confront their culture, and reflect on what it means to be human.

Works Cited

Han, Qinghua (韩清华). 世界美术全集: 绘画卷 [Complete Series of World Fine Arts: Painting Volume]. Z-Library, 2003.

Janson, H. W., and Anthony F. Janson. History of Art, Volume 1. 4th ed., Prentice Hall / Harry N. Abrams, 1991.

Marshall, Francis. Drawing the Female Figure. The Studio Ltd., 1949.

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Looking at Art: An Art History Survey at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Z-Library, 2001.

Schneider, Norbert. The Art of the Portrait: Masterpieces of European Portrait Painting, 1420–1670. Taschen, 2002.