Few animals have been drawn, painted, or sculpted as often—or as lovingly—as the cat. From cave walls to modern sketchbooks, felines prowl through art history as hunters, companions, gods, and symbols of mystery. The ways artists have drawn cats tell us as much about human culture as about the animals themselves.

This is a journey through 30,000 years of feline imagery, blending cave art, Egyptian monuments, Renaissance portraiture, animal drawing manuals, and even the black cat of Halloween lore.

Cats in Prehistoric Art: The Big Predators

The oldest feline drawings aren’t of housecats at all—they’re of their wild ancestors.

In the Chauvet Cave in France (c. 30,000 BCE), walls are filled with lions and panthers, drawn in sweeping charcoal lines.^1 These were not cute companions but apex predators, figures of awe and fear. Artists paid attention to musculature and profile: heads low, haunches taut, bodies ready to strike. The goal wasn’t realism for its own sake but capturing the spirit of the hunt.

These images echo the way animals are studied in Ken Hultgren’s The Art of Animal Drawing, where he emphasizes motion and gesture above detail.^2 Even the earliest cave painters knew that a few decisive strokes could suggest a cat’s tension and grace better than endless decoration.

Egypt: From Gods to Lap Companions

If Chauvet lions were threats, Egyptian cats were deities.

The goddess Bastet, often shown as a lioness or a woman with a cat’s head, represented fertility, music, and protection. By the New Kingdom (c. 1500 BCE), domesticated cats were so revered that they appear frequently in tomb paintings—sitting under chairs, watching over banquets, or catching birds in marshes.

Egyptian artists simplified feline forms into elegant, curving silhouettes. Long tails curled neatly; almond-shaped eyes glowed with divine calm. These conventions influenced later artistic depictions: the idea of the cat as a poised, symmetrical creature of balance.

Cats were so important that killing one—even accidentally—was a capital crime. Archaeologists have found cat cemeteries with thousands of mummified felines, a testament to their sacred role.

Medieval and Renaissance Cats: Mischief and Margin Notes

Cats slip into European manuscripts in the Middle Ages, though not always flatteringly. In illuminated margins, felines chase mice or curl in corners, sometimes drawn with humorous distortion. Monks, it seems, found their monastery cats as distracting as comforting.

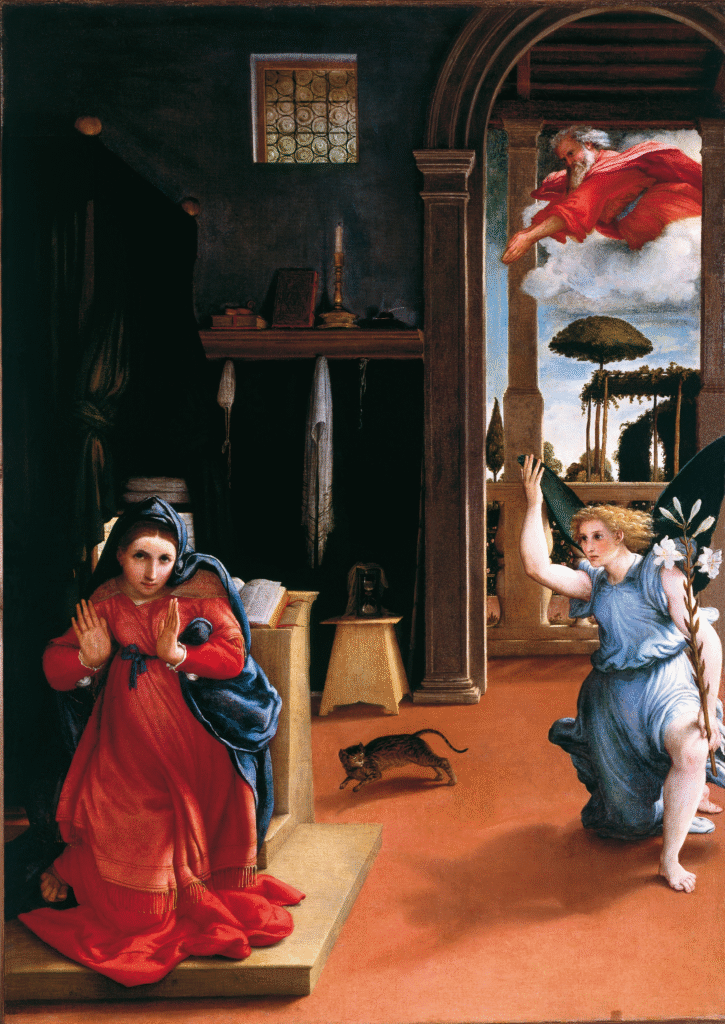

By the Renaissance, cats crept into more formal art. Lorenzo Lotto’s Recanati Annunciation (1527) shows a cat running across the room. Titian sometimes painted cats alongside women, symbols of domesticity—or of sly sensuality.

But even here, hands and feet (the hardest to draw) often got more attention than paws. Artists tended to paint cats in static poses, perhaps to avoid the challenge of their constant motion. As Norbert Schneider notes in The Art of the Portrait, animals in portraits often serve as emblems rather than anatomically precise studies.^3

The Cat in Printmaking and Illustration

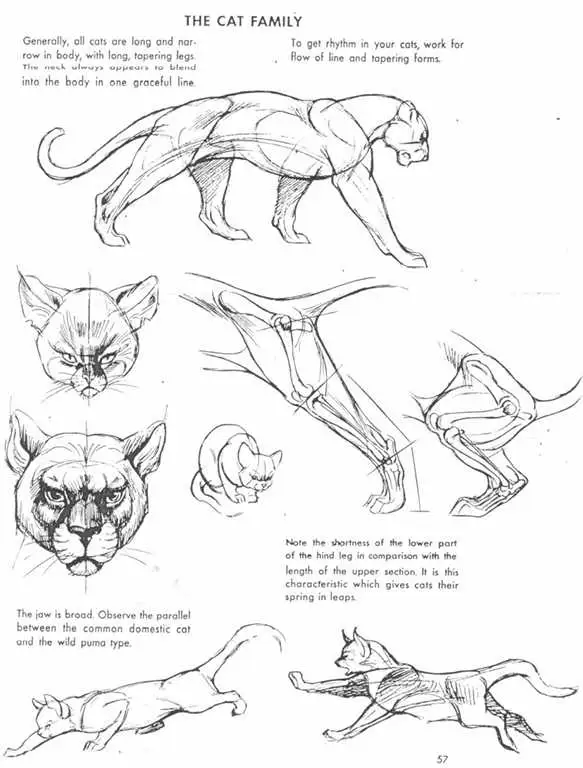

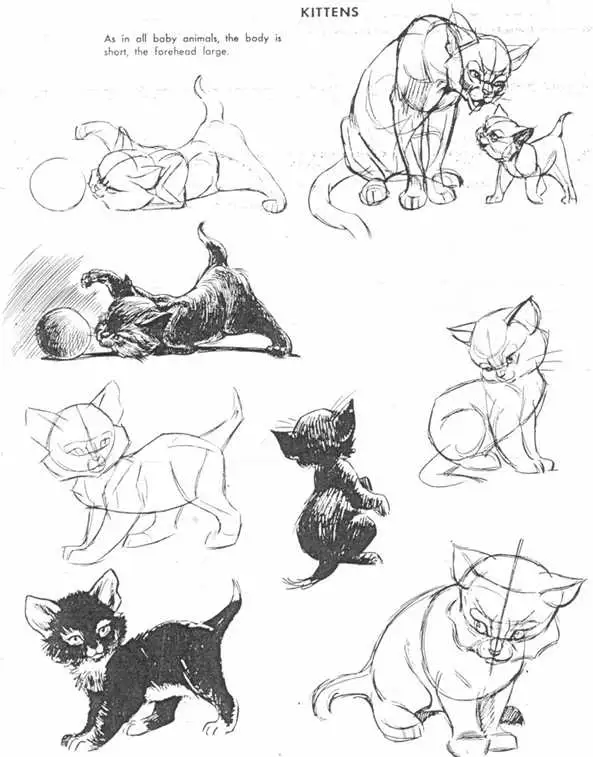

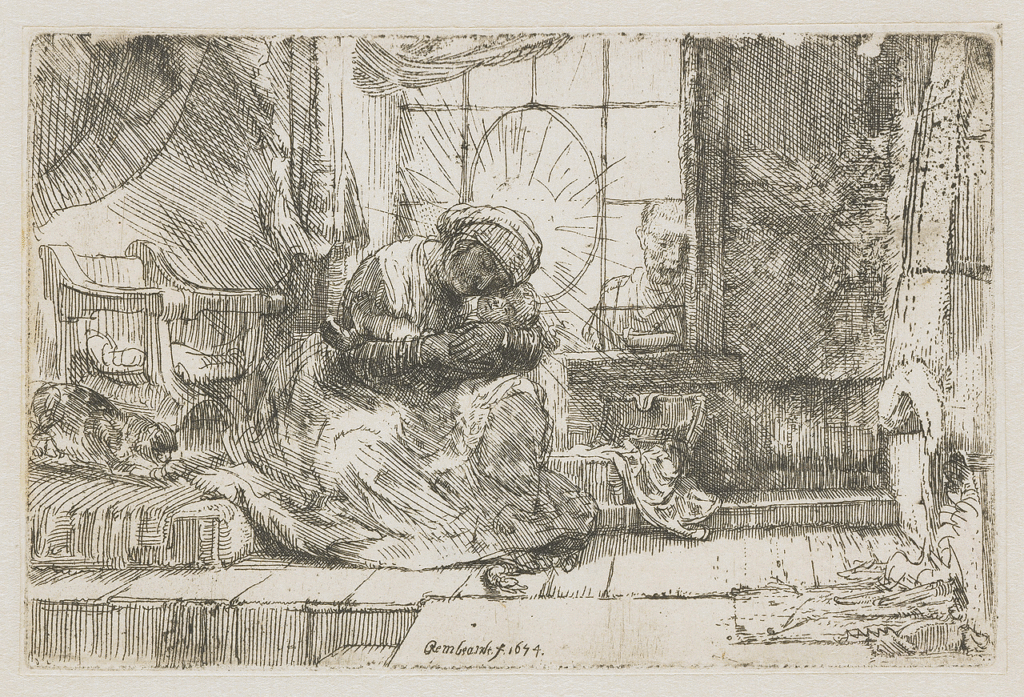

By the 17th century, printmakers like Rembrandt sketched cats with greater liveliness. Etchings show them twisting, arching, or stretching—poses instantly recognizable to any modern cat owner. These studies align with what Hultgren later teaches: break the cat’s body into basic forms—the barrel chest, flexible spine, and tapering legs—before adding detail.^2

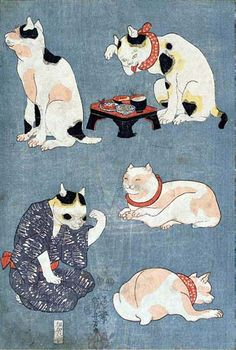

In Japan, ukiyo-e artists like Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861) made cats central to their prints, often anthropomorphized. His series Cats Suggested as the Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō depicts playful cats in human roles, a whimsical testament to their cultural presence.

The Cat in Modern Art

The 19th and 20th centuries brought cats into the modern imagination in ways that were deeply personal, playful, and often provocative. No longer restricted to sacred emblems or hidden marginalia, cats became central to the way modern artists thought about intimacy, rebellion, and the everyday.

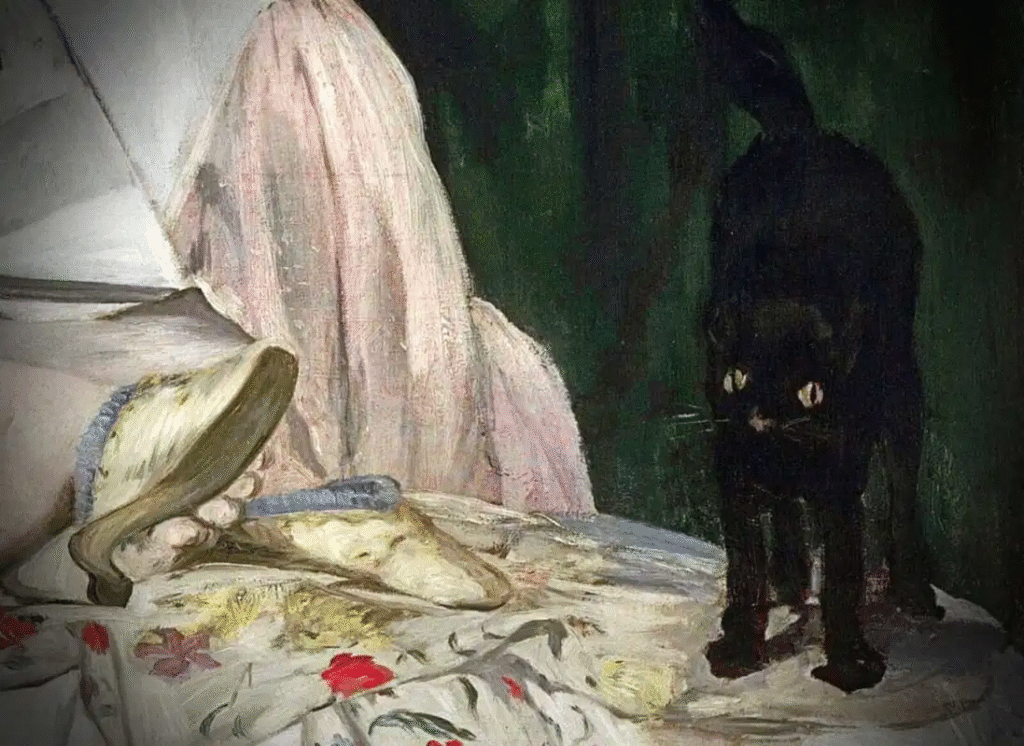

Édouard Manet’s black cat in Olympia (1863) is perhaps the most notorious feline in Western art. Perched at the foot of the reclining courtesan’s bed, the cat arches its back, tail high, with a watchful stare. It is the antithesis of the lapdog often painted in traditional Venus portraits, where a dog symbolized fidelity. Manet’s cat, instead, signals independence, eroticism, and defiance. It reinforces Olympia’s refusal to play the passive muse; both woman and cat meet the viewer’s gaze unapologetically.

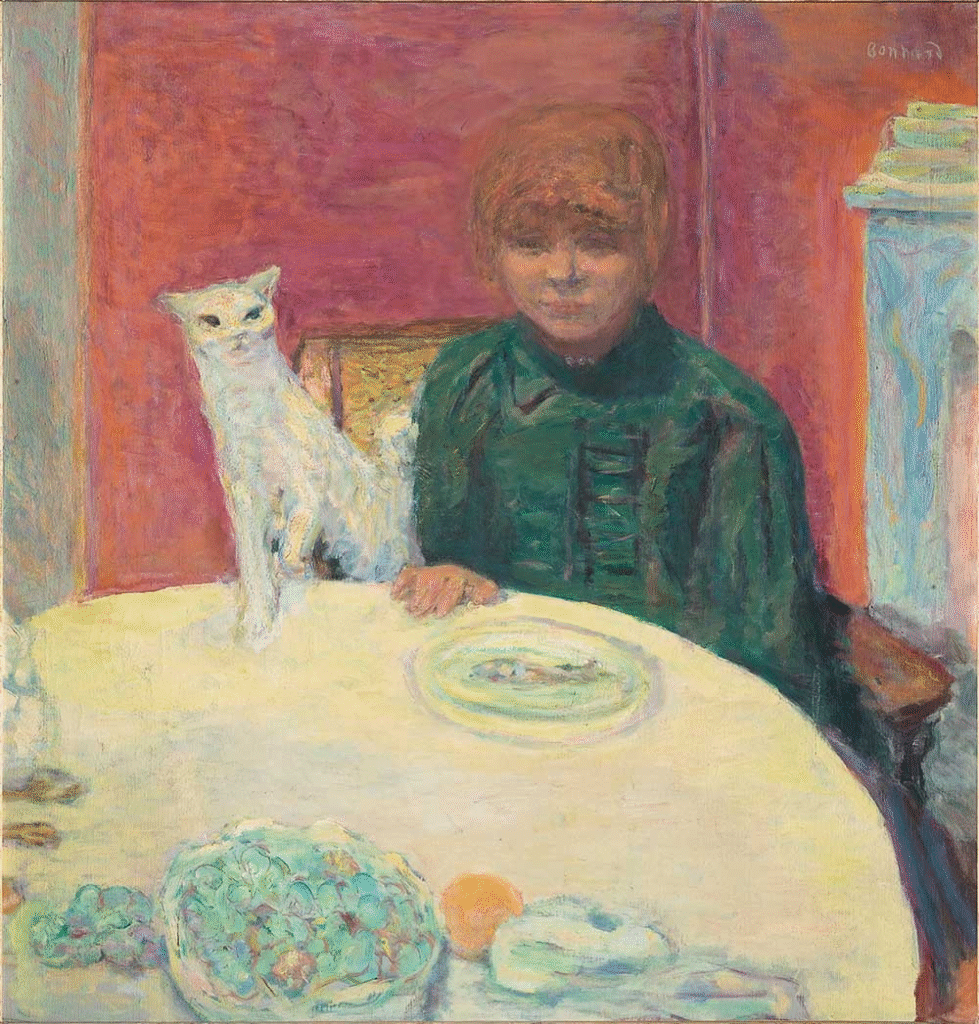

Pierre Bonnard, a member of the Nabis group, painted and sketched domestic interiors suffused with warmth. Cats appear in his works not as symbols but as presences—lounging on tables, stretching across beds, half-hidden in folds of fabric. He captured them with fluid, spare lines, the kind of shorthand Hultgren recommended for animal drawing: a curve for a spine, a flick for a tail.^2 Bonnard’s cats mirror the quiet tenderness of his everyday life, reminders that modern art could find beauty in the familiar.

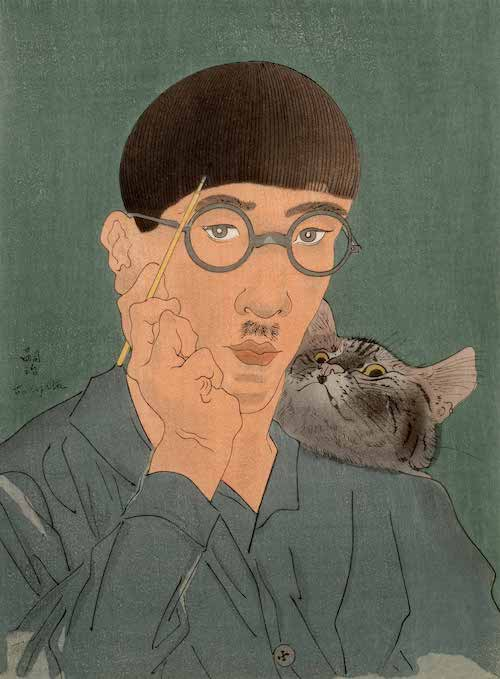

Leonard Foujita, the Japanese-French painter, made cats into his signature subject. His canvases and prints are filled with felines rendered with almost photographic precision: sleek fur, sharp whiskers, wide eyes. Yet he stylized them with decorative outlines influenced by Japanese woodblock prints. Foujita’s cats are simultaneously real and ideal, companions and icons. In doing so, he positioned the cat as an artistic muse equal to the nude figure or the still life.

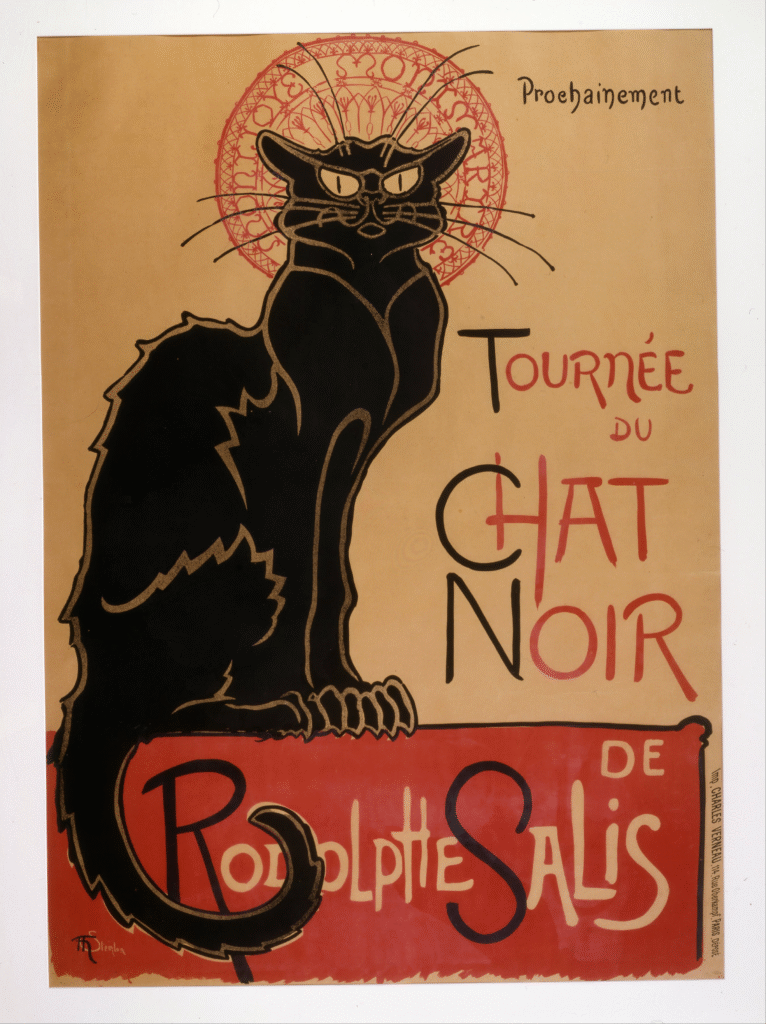

Théophile Steinlen’s Le Chat Noir (1896) poster distilled the cat into a cultural symbol. The angular, black silhouette with glowing eyes became the emblem of Montmartre’s cabaret scene: mysterious, bohemian, and irreverent. It linked the cat with nightlife, artistic freedom, and countercultural identity. Just as Bastet had been worshipped in Egypt, the Chat Noir became the mascot of fin-de-siècle Paris.

Together, these works show how cats in modern art were transformed. They were no longer gods to be worshipped or demons to be feared. Instead, they became companions, muses, and mirrors of human identity—erotic and rebellious in Manet, tender and intimate in Bonnard, iconic in Foujita, and symbolic of urban bohemia in Steinlen. In the modern era, the cat was fully integrated into art as part of lived experience: playful, mysterious, and always a little aloof..

Drawing Cats: The Artist’s Challenge

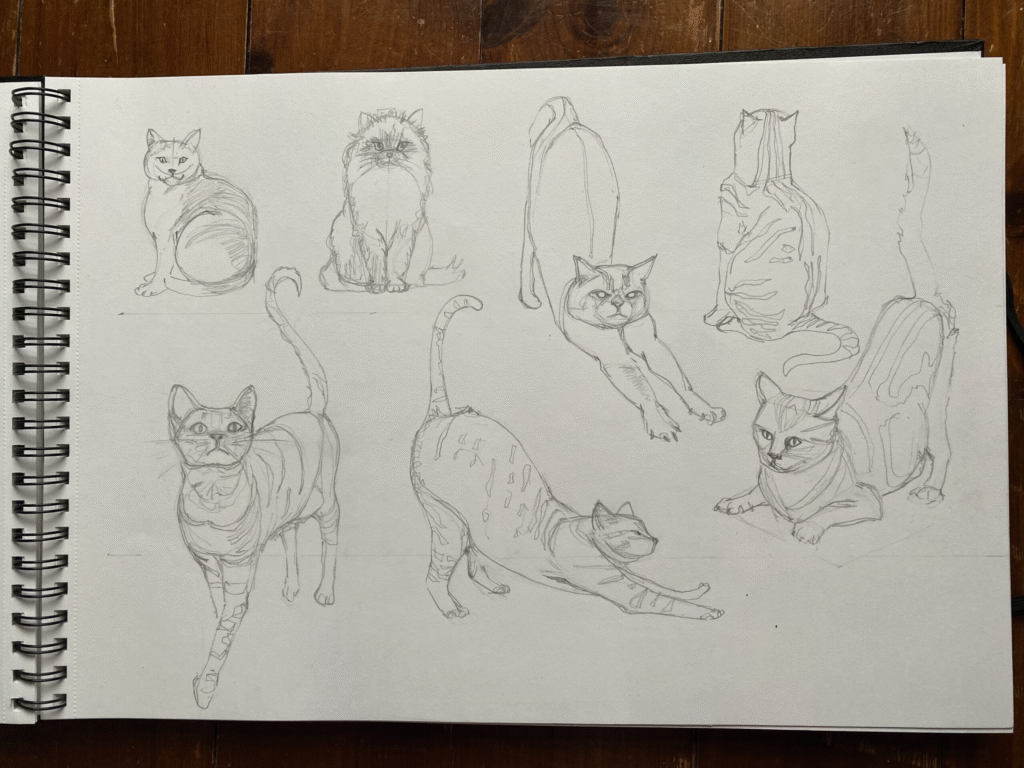

For artists, cats pose unique technical challenges. Unlike dogs or horses, their anatomy is built on extreme flexibility. The spine acts like a spring; the shoulder blades float; the legs tuck and stretch with elastic range.

Ken Hultgren warns that cats require more attention to gesture than any other animal.^2 A cat at rest may look simple, but capture it mid-leap or mid-pounce, and suddenly every curve matters. Artists must learn to exaggerate the arch of the back, the tuck of the hindquarters, the rhythm of the tail.

Lauricella’s anatomical breakdowns in Morpho (though focused on humans) remind us of the importance of simplification: cylinders for legs, spheres for joints, a fluid central line of action. The same applies to felines: reduce them to geometric forms, then build up fur and detail.

The Black Cat: Halloween’s Familiar

If the Egyptian cat was sacred, the medieval European cat—especially the black one—was feared.

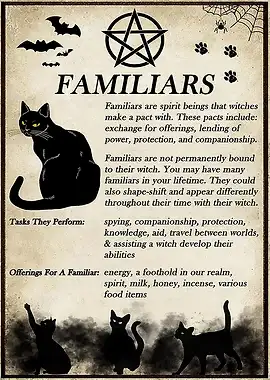

By the late Middle Ages, cats had become associated with witches, superstition, and bad luck. Black cats, in particular, were thought to be witches’ familiars or even witches in disguise. This lore survives in Halloween decorations to this day: silhouettes of arched-back cats with glowing eyes.

From an artistic perspective, the Halloween black cat is almost a logo: simplified, bold, and graphic. Its arched silhouette recalls Egyptian poise, while its spooky role echoes Chauvet’s lions. It’s the universal cat distilled into a seasonal symbol of mystery and fear.

Why Cats Endure in Art

So why do cats keep showing up across 30,000 years of art? The answer lies in their contradictions—and in the way those contradictions mirror our own.

They embody dualities. Cats are creatures of paradox: both domestic and wild, affectionate and aloof, graceful and violent. The cave lions of Chauvet showed them as predators to be feared, while the Egyptian Bastet represented fertility and protection. In Renaissance portraits, they could symbolize sensuality, while in Halloween imagery they became omens of bad luck. The cat absorbs whatever meaning the artist or culture projects onto it, which is precisely why it survives as an enduring symbol.

They test artists. Capturing a cat’s motion is as challenging as drawing hands or feet—it requires both anatomical knowledge and sensitivity to gesture. From Dürer’s etchings to Bonnard’s sketches, artists have found that a single curve or misplaced paw can turn elegance into awkwardness. Their flexible spines, coiled energy, and sudden bursts of motion make them perfect studies in line and rhythm. Ken Hultgren’s The Art of Animal Drawing stresses this: cats demand that an artist learn to “see the flow before the fur.”^2

They fascinate us. Few animals hold human attention so completely. Ancient Egyptians mummified cats; medieval monks doodled them in manuscripts; Manet painted them as provocateurs; Steinlen turned them into the emblem of Paris nightlife. Today, the tradition continues in memes and TikTok videos—the artistic impulse remains the same. Humans can’t stop watching cats, so we can’t stop drawing them.

The universal cat, then, is more than an animal. It is a mirror of human imagination: predator, god, pet, symbol, and muse. Wherever humans draw, paint, or carve, the cat is sure to be nearby—sometimes curled in a lap, sometimes arching its back in defiance, but always present, always demanding to be seen.

Conclusion

From lions on cave walls to curled-up housecats in sketchbooks, felines have stalked through art for millennia. Each era reshaped them: awe-inspiring in Chauvet, divine in Egypt, comical in manuscripts, symbolic in Renaissance portraits, bohemian in Paris, spooky on Halloween.

And through it all, artists have wrestled with the same challenge: how to capture the cat’s elusive, flexible, mercurial essence. Whether in charcoal on limestone, oil on canvas, or quick pencil lines in a sketchbook, the cat remains a test of observation, style, and imagination.

That’s why cats remain universal—not just in art, but in human culture. They’re everywhere, and they always will be.

References

- Han, Q. (2006). Complete Series of World Fine Arts: Painting Volume. Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House.

- Hultgren, K. (1951). The Art of Animal Drawing. New York: Watson-Guptill.

- Schneider, N. (1994). The Art of the Portrait: Masterpieces of European Portrait Painting 1420–1670. Köln: Taschen.