There’s an old joke among art students: “If you can’t draw hands, just hide them behind the back. And if you can’t draw feet, just crop the picture.” Anyone who has tried to draw seriously knows why the joke stings—hands and feet are some of the most dreaded subjects in figure drawing. Even seasoned artists confess they avoid them. But the truth is, these appendages are also the most expressive, the most human, and the most revealing parts of the body.

Why are hands and feet so difficult to draw, and how can an artist get better at them? The answer lies in a mix of anatomy, psychology, and a long history of artists struggling (and sometimes succeeding) with these forms.

Why Hands and Feet Are So Difficult

First, the obvious: hands and feet are complicated.

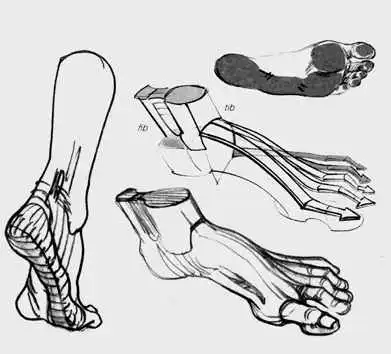

Each hand contains 27 bones, over 30 joints, and more than a hundred ligaments. The foot isn’t much simpler: 26 bones, 30 joints, and a complex arch system. Both are designed for constant motion, weight distribution, and delicate control. Trying to capture this complexity with a pencil means distilling hundreds of anatomical details into a few convincing lines.

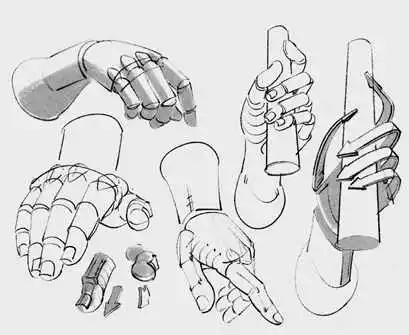

In Morpho: Hands and Feet, Michel Lauricella emphasizes starting from simplified structures—blocks for palms, wedges for feet, cylinders for fingers and toes—because otherwise you drown in details.^1 Without simplification, you end up either stiff or confused.

But the challenge isn’t only anatomical. It’s also expressive.

- Hands are emotional transmitters. They can clench in anger, reach in longing, collapse in exhaustion. In fact, studies show people often watch a speaker’s hands almost as much as their face in conversation. If your drawn hand looks wrong, viewers instantly feel the failure.

- Feet are about weight and balance. Get them wrong, and the entire figure seems to float or wobble unnaturally. The foot’s arch, heel, and toes distribute mass in subtle but crucial ways.

And then comes the nightmare of perspective. Hands and feet constantly foreshorten: a finger pointing outward, a heel stepping forward. Every angle shifts proportion, making them look stubby or elongated if you’re not careful.

Finally, there’s the psychological trap. People are wired to notice faces and hands. We forgive sloppy elbows or knees, but hands and feet are too familiar. Any error, and your viewer immediately spots it.

Classical Struggles and Solutions

Art history is full of evidence that hands and feet have always been difficult.

- Greek and Roman sculpture often idealized bodies but simplified extremities. Marble gods stand with majestic torsos, yet their hands are curiously smooth, sometimes clenched in neutral gestures rather than active ones.

The figure exemplifies Polykleitos’ canon of ideal proportions. The torso and stance are rendered with remarkable anatomical harmony, yet the hands and feet are relatively simplified. The right hand, which once held a spear, is smoothed and neutral rather than expressive, showing how Greek sculptors often prioritized overall balance over detailed extremities

- Renaissance breakthroughs changed this. Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical notebooks are filled with hand studies—knuckles, tendons, foreshortened palms. He treated the hand as a “second face,” capable of expression and worthy of obsessive study. Albrecht Dürer produced engravings like Praying Hands (1508), where every tendon is carefully articulated.

- Baroque painters such as Caravaggio and Rubens made hands dramatic tools. In Caravaggio’s The Calling of St. Matthew (1599), Christ’s pointing hand dominates the composition, echoing Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. Rubens painted fleshy, dynamic hands that swirl in motion, almost as recognizable as the faces.

- Portraiture between 1420 and 1670, as Norbert Schneider notes, often used hands to signal class and identity.^2 A gloved hand meant wealth and leisure, while an ungloved one might show labor or scholarship. To omit the hands would have been to omit character.

Even with centuries of examples, artists still struggled. Many painters positioned subjects with hands hidden under drapery or folded discreetly to avoid anatomical pitfalls.

The sitter’s hands are visible but posed in a controlled, almost schematic way, holding instruments of his trade as an astronomer. Holbein avoids unnecessary anatomical complexity—fingers are simplified and partly obscured by objects—allowing the emphasis to remain on the sitter’s identity and profession rather than the raw difficulty of depicting hands.

What Modern Anatomy Guides Teach

Michel Lauricella’s Morpho: Hands and Feet is one of the clearest modern guides for artists wrestling with extremities. His method isn’t about drawing every tendon—it’s about breaking forms down.

- The hand: Think of the palm as a block, thick at the base and tapering slightly at the fingers. Fingers are cylinders, each joint slightly shorter than the last, radiating not in parallel but like a fan. The thumb is unique: a block set at an angle, capable of opposition.

- The foot: Imagine a wedge. The heel is the back anchor, the toes the front fanning blocks. The arch curves upward, meaning a foot is never flat on both sides.

Lauricella layers drawings from skeleton to muscle to surface. This way, you see not just what a hand looks like, but why it looks that way. The knuckles protrude because bone is shallow beneath the skin; the ball of the foot bulges because of thick pads of fat cushioning weight.

The key lesson is simplification first, detail later. A beginner who tries to copy every wrinkle on a palm will fail. But one who starts with a cube and adds finger cylinders can succeed.

Common Mistakes Artists Make (Deepened)

Even seasoned artists fall into traps when drawing hands and feet. These aren’t just technical errors—they’re misunderstandings of form, proportion, or function that break believability.

1. Fingers drawn the same length

Many beginners line fingers up like fence posts. But in reality, the fingers descend in a gentle arc: the middle finger is the longest, the index and ring taper off, and the pinky is shortest. Lauricella shows how the fingers radiate outward from the palm like spokes of a wheel rather than marching in parallel lines.^1 When you ignore this rhythm, you get robotic, lifeless hands that don’t match how people perceive their own.

2. Ignoring the thumb

The thumb is not “just another finger.” It has a separate bone structure and an opposable joint that allows it to pivot across the palm. That mobility is why the human hand can grip tools, play instruments, or gesture so expressively. Treating it as an afterthought often leads to awkward, stiff drawings where the thumb looks glued to the side of the palm. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci studied the thumb obsessively, sketching dozens of variations of its fold and grip.

3. Flat feet

When beginners draw feet, they often default to a “shoe print”—a flat oval with stubby toes. But feet are sculptural forms: the arch lifts, the heel bulges, and toes taper in length and volume. Without the arch, the figure seems unbalanced, like it’s sliding on ice. Classical sculptors emphasized the tension in the foot’s arch to show energy, while Degas’ ballerinas rely on this curve to communicate poise and balance.

4. Avoidance

The most common mistake isn’t drawing them incorrectly—it’s not drawing them at all. Artists through history have hidden hands in sleeves, tucked them into folds of drapery, or cropped feet out of the frame. Even accomplished modern illustrators sometimes cheat by placing objects (books, weapons, or smoke) over hands. While this can work compositionally, it also stunts growth. The only way to master extremities is to face them head-on, not to dodge them.

Exercises to Master Hands and Feet (Deepened)

If mistakes are predictable, the remedies are equally well-known: practice and focused observation. But not all practice is equal. The following exercises build skills progressively, from loose gestures to structural understanding.

1. Gesture Studies

Set a timer and draw 30 hands in 30 minutes. Work quickly, focusing on the “attitude” of the hand—the splay of fingers, the curve of the palm, the clenched or relaxed energy. Gesture drawing strips away the fear of detail. As Lauricella notes, capturing the block of the palm and the overall silhouette matters more than fingernails at this stage.^1 Over time, gesture studies train your eye to see hands and feet as expressive shapes rather than intimidating puzzles.

2. Silhouette Drills

Paint or fill in black shapes of hands in various poses. If the silhouette alone communicates the gesture—open palm, pointing, clenched fist—then you know the drawing is strong. This is a principle used in animation: if a character’s hand reads clearly in silhouette, it will read in motion. The same applies to feet: a dancer’s pointed toe or a runner’s heel strike should be obvious even without interior detail.

3. Skeleton Overlays

Print or photograph hands and feet, then draw the skeletal structure over them. Identify the carpals, metacarpals, and phalanges in the hand; the tarsals, metatarsals, and phalanges in the foot. This builds a mental link between what you see on the surface and what lies beneath. Once you know that a protruding bump is actually the head of the metacarpal bone, you stop guessing and start drawing with intention.

4. Copy the Masters

Reproduce studies by Leonardo, Dürer, or Michelangelo. Dürer’s Praying Hands (1508) remains a masterclass in tension, proportion, and tendon visibility. Michelangelo’s chalk studies of feet show how weight distribution creates bulges and curves. Copying teaches not just anatomy but also interpretation—how artists chose what to emphasize or simplify for expressive power.

5. Daily Sketch Habit

Your best models are always available: your own hands and feet. Keep a sketchbook nearby and draw them in idle moments—while on the phone, waiting in line, or during warm-ups. Try odd angles: foreshortened views, overhead, curled under. The more angles you practice, the more confident you’ll feel. Consistency is key. As Lauricella suggests, drawing five quick hands every day for a month will teach you more than laboring over one “perfect” drawing a week.^1

Beyond Accuracy: Hands and Feet as Storytellers

Technical skill matters, but hands and feet go beyond anatomy. They are narrative devices.

- Hands as emotion: Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam is as much about the nearly touching hands as the figures themselves. Van Gogh’s Peasant Hands are thick, rough, and aching with labor, telling more than a face ever could.

- Feet as grounding: Rodin’s sculptures often emphasize weight through massive feet, anchoring the emotional intensity of his figures. Degas’ ballerinas, conversely, are defined by delicate pointed feet, embodying grace.

- Comics and graphic novels: David Chelsea reminds artists that hands dramatize dialogue, while feet establish space and action stances.^3 A superhero landing pose is unthinkable without foreshortened feet punching into the ground.

In other words, hands and feet aren’t just difficult—they’re essential for meaning. Ignore them, and your figures lose life. Master them, and you command storytelling power.

Conclusion

Hands and feet are the hardest parts of the body to draw because they are the most visible, the most expressive, and the most structurally complex. They challenge artists on every level: anatomy, perspective, symbolism, and psychology. But that difficulty is also why they matter so much.

The solution isn’t to avoid them but to embrace them. Study their structure, as Lauricella teaches. Learn from history, from Leonardo to Dürer to Van Gogh. Practice relentlessly, from quick gestures to careful master copies.

The old art-school joke—hiding hands and cropping feet—only works in sketches. If you want to grow, you have to put them front and center. Because once you conquer them, hands and feet stop being a weakness and become your strongest storytelling tools.

References

- Lauricella, M. (2014). Morpho: Hands and Feet (Anatomy for Artists). Paris: Eyrolles.

- Schneider, N. (1994). The Art of the Portrait: Masterpieces of European Portrait Painting 1420–1670. Köln: Taschen.

- Chelsea, D. (1997). Perspective for Comic Book Artists. New York: Watson-Guptill.

- Janson, H. W., & Janson, A. F. (1991). History of Art, Vol. 1. New York: Harry N. Abrams.